Science of Metabolic Typing:

An Excerpt from Dr. Nicholas Gonzalez's International Award Winning Book, Nutrition and the Autonomic Nervous System: The Scientific Foundations of The Gonzalez Protocol®

Dr. Francis Pottenger Sr.'s book, Symptoms of Visceral Disease, addresses the field of neurophysiology and remains one of the least read—and perhaps one of the most important—books in medicine with editions spanning the period 1919 to 1944.

Pottenger was one of the pioneers describing the function of the autonomic nervous system, the elaborate network of nerves that connects to, and controls the metabolism of, all the tissues, organs, and glands of the body. The word autonomic was first used by J. N. Langley, the English scientist, during the early years of the twentieth century as a take on the word automatic, to describe the nerves that can function automatically, without the direct intervention of our conscious brain. The autonomic system directs processes such as blood pressure and heart rate, immune function, and the activity of all the endocrine glands in the body, including the thyroid and adrenal glands. Autonomic nerves directly control all digestion, including the secretion of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, the production and release of digestive enzymes from the pancreas, the secretion of bile from the liver, the movement of food along the intestines, and the absorption and utilization of nutrients.

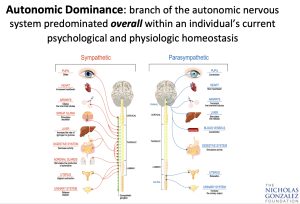

The autonomic system can itself be divided into two components: the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches, which are very distinct anatomically and functionally. Each branch connects to every tissue, organ, and gland in the body but produces opposing effects. For example, the sympathetic system when active increases heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiac output and stimulates the endocrine glands, such as the thyroid and adrenals. Adrenaline production increases.

However, when sympathetic nerves fire, the entire digestive system turns off: the pancreas stops secreting enzymes, the liver stops producing and releasing bile, and peristalsis (the rhythmic contraction of the intestines that moves food along) slows down. Blood shunts away from the intestinal organs to the muscles and the brain. In addition, the sympathetic neurons inhibit immune function. Overall, the sympathetic system tends to stimulate metabolism and in effect cause the breakdown of tissues, such as fats and muscle, to produce energy.

Traditionally, scientists describe the sympathetic nervous system as the “flight or fight system,” the nerves that activate during any physical or emotional stress. An active sympathetic system shifts metabolism to aid the body in dealing with a stressful event. Heart output increases, to provide a quick flow of oxygen, energy, and nutrients where it is needed most: to the brain for quick thinking, and to the muscles for rapid physical response. Activities not crucial in a moment of stress, such as digestion, shut down so that energy can be conserved for more essential needs.

In contrast, the parasympathetic system, when it fires, slows the heart rate, reduces blood pressure, and turns on the entire digestive tract. The production and secretion of all digestive juices increases, including acid in the stomach, pancreatic enzymes, and bile from the liver. Peristalsis, the movement of digestion products through the intestines, becomes strong and blood shunts away from the muscles to the intestines, so that the digestion, absorption, and utilization of nutrients proceed efficiently. In addition, parasympathetic nerves enhance immune function and slow down the secretion of thyroid and adrenal hormones. Overall, metabolism slows down.

The parasympathetic system is the regeneration system of the body, directing the digestion of food and the absorption and utilization of nutrients to allow for the repair and rebuilding of tissues and organs. This system is especially active at night, during rest, when the body recovers from the damage of the day’s activity.

Though scientists think of the sympathetic system as the “stress” system and the parasympathetic nerves as being more involved with routine metabolism, in fact the two systems operate together, in every moment of our lives, adjusting metabolism to suit each situation we face. This system allows us to adapt, constructively, to the physical and emotional world around us.

Pottenger did much to outline the intricate function of the two branches of the autonomic nervous system. In that work, he was truly brilliant. But he also made a series of observations that directly relate to my treatment approach some fifty years later. Pottenger was an excellent observer, involved not only in research but also in patient care. During his early clinical work in the 1920s, Pottenger noticed that some of his patients were born with a very strong, perhaps overly developed, sympathetic nervous system and a correspondingly weak parasympathetic system.

In these patients, all the tissues, organs, and glands normally stimulated by the sympathetic system, such as the heart, the muscles, the left hemisphere of the brain, and the endocrine glands, were very highly developed, very efficient, perhaps too active. In contrast, the tissues, organs, and glands normally stimulated by the weak parasympathetic system—such as the right brain hemisphere and the entire digestive system, including the pancreas and the liver—were very weak and inefficient.

In these “sympathetic dominants,” Pottenger identified a series of ailments related to their autonomic imbalance. Emotionally, these patients were very anxious, irritable, reactive, and easily upset, in keeping with their overly developed stress response system and high levels of circulating adrenaline from sympathetic nerve firing. Such patients tended to be disciplined and good at routines. Structurally, they were usually thin, because of their strong thyroid and adrenal function. They needed little sleep and often slept lightly and fitfully. In these patients, Pottenger reported strong muscles but terrible digestion: such patients were subject to a wide range of digestive problems such as food intolerances, ulcers, colitis, irritable bowel, chronic ingestion, and hiatal hernias.

In other patients, Pottenger identified a strong parasympathetic system and a correspondingly weak sympathetic system. In this group, Pottenger claimed, all the tissues, organs, and glands normally stimulated by the strong parasympathetic system—such as the right hemisphere of the brain; the entire digestive tract, with the pancreas and liver; and the immune system—were overly developed and overly active. However, in these patients, the organs controlled by the weak sympathetic system, such as the heart, the muscular system, and the endocrine glands such as the thyroid, were very sluggish and inefficient.

Pottenger described these patients as calm, emotionally stable, and even keeled, very slow to anger but at times prone to depression. They were, Pottenger said, undisciplined but very creative. This group suffered degenerative musculoskeletal illnesses, as well as low adrenal and low thyroid function, correlating with their weak sympathetic tone. Such patients had a diminished capacity to deal with acute stress, and as a result of their low endocrine output, such patients could easily become overweight. Even minor stresses could be exhausting.

Pottenger described a third group, with a more balanced autonomic nervous system and equally strong and equally efficient sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. In addition, all the tissues, organs, and glands stimulated by these nerves in this group were equally developed, equally efficient, and equally active. These balanced people had a personality profile between the two extremes. They dealt with stress efficiently but were not overly reactive; disciplined when needed, they could also be creative. Their digestive and endocrine systems were very efficient, neither overly strong nor weak. Of the three groups, balanced patients were the most resilient and generally healthiest. If stressed enough, they could suffer illnesses of either the sympathetic or the parasympathetic group but usually in a less severe form.

By the 1930s, Pottenger realized not only that did these different groups—the sympathetic dominants, the parasympathetic dominants, and the balanced patients—differ remarkably in their basic metabolism, personalities, and health profiles, but also that each group responded quite differently to specific nutrients. Pottenger spent many years studying the effect of individual nutrients, particularly the minerals calcium, magnesium, and potassium, on autonomic function. He found that magnesium tended to block sympathetic activity, while calcium stimulated sympathetic firing. He discovered, in 1936, that potassium activated parasympathetic nerves. Much of his innovative work has, seventy years later, been confirmed. Scientists now know that magnesium does block—and calcium does stimulate—sympathetic nerve firing, while potassium stimulates parasympathetic activity, just as Pottenger claimed.

After years of trial and error, Pottenger learned that he could use these three nutrients to bring an out-of-balance autonomic system into balance. And, as the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems came into equilibrium, his patients felt better and did better, whatever their underlying disease might have been. For example, he learned that sympathetic-dominant patients did very well with the minerals magnesium and potassium, which respectively blocked their strong sympathetic nerves while stimulating the weak parasympathetic outflow. But these sympathetic patients did very poorly with calcium, which stimulated their already too strong sympathetic system.

Parasympathetic-dominant patients, on the other hand, did very well with large doses of calcium, which stimulated their weak sympathetic system. But such patients did very poorly with supplemental magnesium and potassium. With the careful use of these basic nutrients, Pottenger claimed, he could bring his patients to health.

Increasingly, Pottenger believed that disease, whatever its form, from allergies to cancer to eczema, had as a major cause autonomic system imbalance. Health, he came to believe, resulted when the two branches of the autonomic system, and in turn, all the tissues and organs they control, were equally strong, efficient, and in physiological balance.

- Nicholas Gonzalez, M.D.